|

"She can't be Jewish: she's blonde." That line, poised dramatically between comment and comedy, is a swift, deft observation of British attitudes in the Sixties. It is actually the baffled response of Jacqueline du Pré's father to the news that his daughter is converting to Judaism, in the film Hilary and Jackie. The same high-wire act is maintained throughout CP Taylor's 'Good'. The playwright himself deseribed it as a "tragedy which I have written as a musical comedy". Taylor dares to use the music playing in the mind of his central character to dramatise one of the most crucial issues of the 20th century. Set in Germany in the 1930s, 'Good' goes a long way towards answering the question of how ordinary citizens became implicated in the Final Solution.

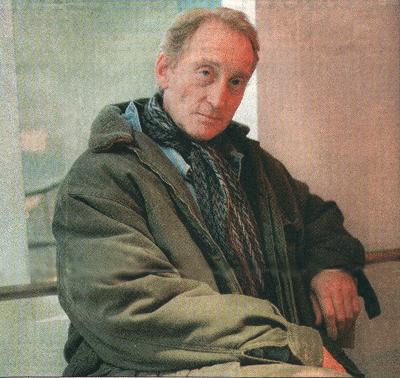

The other link between this and Hilary and Jackie is Charles Dance. A couple of years before the original production of 'Good', while touring with the RSC, Dance had gone to Buchenwald. "A sobering experience, to say the least," he says, quietly. "Then, last year, my wife went to Auschwitz with some old neighbours of ours who lost many of their family in the Holocaust. Jo is a goy but sort of an honorary Jew, really. It had a profound effect on her, as it would, and she came back and immersed herself in the subject. We've been talking about it and what led up to it in relation to what's happening in Rwanda and Kosovo." Although 'Good' is located very specifically in time and place, its power lies in the fact that it's much more than just a slice of history. The dramatisation of the difficulty of trying to live one's life in the teeth of moral and political dilemmas resonates in the present. That's what most appeals to Grandage who cast Dance partly for his charm: audiences want to like him. That has been both his fortune and his fate. Ever since his beautifully understated, career-making performance in 'The Jewel in the Crown', Dance has suffered from type-casting. "Well," he counters, gracefully, "maybe not 'suffered'. When I joined the RSC someone said: 'I can see you're a fuckin' lord actor.' I'm not protesting about it," he shrugs, "but I never asked for that string of roles." True enough. Only the tiniest handful of actors get to create their own opportunities. "You do what you're offered. Only once in 30 years have I known what I was going to be doing next and that was because I had a holiday during the 18 months of 'Jewel in the Crown' and something came along after it." His pale grey eyes turn rueful. "There's a limit to how many ways you can play the romantic lead." At the beginning of the film Pascali's Island, his character is pointed out: "I take it you are referring to the Englishman," is the decription. As far as most audiences and casting directors are concerned, that's him. From Meryl Streep's husband in the film of David Hare's Plenty (1985) to ITV's 'Rebecca' (1996) - he even played a variation on the theme in Alien 3 - "upperclass, still-waters-run-deep" has been his job description. When he starred with Trevor Howard in White Mischief you realised that if anyone were foolish enough to remake Brief Encounter, they'd be straight on the phone to Dance. All those lean, fine-featured matinee idols in white linen, you could be forgiven for thinking he had a Merchant-Ivory birthmark. The irony amuses him no end. "I'm as common as muck, me. I think my mother may have married vaguely above her station ... but not that much." In fact, his career has been studded with lesser-known performances outside that narrow brief from playing DW Griffith in the Taviani brothers' beguiling Good Morning, Babylon to "a couple of barking lunatics - verging on paedophilia in one case - and a psychopathic Southern redneck in a film that never saw the light of day". Yet even in the trademark roles there's often an unexpected quality. Most leading men only ever play good guys - try imagining Harrison Ford as a baddie - but look at Dance as the heartless philanderer in White Mischief. He's accurately described as "a frightful cad ... the most amusing man in Kenya" but he turns your sympathies towards him. This ambivalence makes him perfect casting for 'Good', playing a "good" man, a literature professor who winds up in the midst of the Nazi nightmare. "It goes at a phenomenal lick, you'll be out in the pub by 10pm," he laughs, bravely making light of the fact that this part is a serious challenge: he's onstage throughout. All the more taxing considering that he's only done two stage roles in the last nine years: 'Coriolanus' for the RSC in 1989 and Vershinin in 'Three Sisters' in Birmingham last Autumn. His teenage year almost stymied his acting altogether. After enjoying being in school plays he went to art school, his adolescence having been scarred not by acne but by a stammer. As his self-confidence grew, the stammer dwindled. But upon returning to Plymouth he realised he didn't want to be a graphic designer. So for two years he teamed up with two men who'd coached a couple of his friends into Rada. "They were like gurus to me," he says, simply. "Leonard, Martin and I worked in the back room of a pub and in their funny little cottage down in Devon for two years working through Shakespeare, Shaw and Beckett with dusty old manuals to try and improve my posture and my understanding of what the body does. They taught me more than just acting. It was a whole attitude to life." He does, however, admit that he didn't have the advantage of learning from his peers. That may account for the criticism of distance which dogs him. But it may also explain his controlled relationship with the camera. Unfashionably among British actors, while relishing the emotional and physical potential of theatre acting, he loves film. "For my money, there's a much stronger link between film and theatre than between theatre and television. Film you look up to, TV you look down to. TV's this sort of factory churning stuff out," he adds, citing David Hare's line in 'Amy's View' where Judi Dench disparages "being taken no notice of in 10 million homes". He even counters the claim that unlike film, theatre is in permanent wideshot. "The proscenium arch is like a big screen, but the actor and director together choose the lens and show you what to focus on. In smaller spaces like the Donmar, there's the opportunity to work in detail in the way one can when someone snaps a 75mm lens on you." The flip side of film is that "we tend not to breed great screenwriting. As a screen actor, you have to expend an inordinate amount of energy trying to make a silk purse out of a pig's ear. But we write bloody good plays. With something like 'Good', you've got the silk purse so you can put all your energy into serving it well. I do take the work very seriously." He stops, shaking his head at his own earnestness, and smiles. "Hopefully, I don't take myself that seriously." |

A powerfully theatrical examination of the dangers of the liberal position, it was voted one of the plays of the century in the recent National Theatre poll and remains the masterpiece among the 70 plays of this neglected writer who died, aged 52, just two months after the play's 1981 RSC premiere at the Donmar Warehouse. Tomorrow it returns to the venue in a production by Michael Grandage.

A powerfully theatrical examination of the dangers of the liberal position, it was voted one of the plays of the century in the recent National Theatre poll and remains the masterpiece among the 70 plays of this neglected writer who died, aged 52, just two months after the play's 1981 RSC premiere at the Donmar Warehouse. Tomorrow it returns to the venue in a production by Michael Grandage.